Post by slash on Jul 9, 2010 11:02:42 GMT -5

Sports Illustrated:

Professional sports can be awfully unforgiving to athletes who don’t deliver. And the weight of the basketball world was lumped onto the shoulders of an athletic, well-rounded power forward with an average name: Joe Smith.

When you’re drafted 1st overall, you are expected to be extraordinary, a game changer, a veritable star. But drafting players is an inexact science. The draft is based on data gathered on young men who dominate at the high school and college level, where they are essentially men among boys. What scouts and general managers often cannot measure are the intangibles: the will to win, the willingness to play hurt, the drive to improve and to leverage your skill set into a successful role in the professional world, where everything is faster, rougher, and more unforgiving. Sure, you can show the will to win in the NCAA tournament, but on any given play, college players make at least a half-dozen positioning errors that make it easy for a superior peer to exploit. Professionals might make the same mistake, but they are quicker to recover and more willing to pound you in the process. The greater likelihood is that savvy pros will feign a weakness, and instead quickly deny you the opportunity you seek.

That’s why, in retrospect, basketball experts viciously attacked the Philadelphia 76ers for passing on Penny Hardaway, Jamal Mashburn, Vin Baker, and Allan Houston to draft Shawn Bradley, who has carved out a decent role in this league, but has never been able to come close to justifying his selection at #2 with so much superior talent available.

It is the inexact science of drafting that led to the creation of Joe Smith, the oft-maligned, steady power forward who was chosen instead of Kevin Garnett, Antonio McDyess, and Jerry Stackhouse—all superior players in terms of mental strength and output. Scouts looked at Joe Smith and saw a younger player oozing with talent, a consensus Player of the Year and a future star. He had range, he had athleticism, he had a nice array of moves, and he had a level head. They reasoned that choosing a sophomore allowed teams to develop a young star early and maximize his potential, rather than picking a senior, who can be seen as a prospect with stunted growth from playing against college-level talent for so long. If Smith panned out, basketball executives argued, he could become a real superstar, a guy with a fantastic inside-outside game with the amiability that would make marketing executives drool. Smith could shoot threes, run with small forwards, leap over players, and finish dunks with aplomb.

But choosing a young player has its drawbacks. Barely 20 when drafted, Smith had no clue what it was like to carry a team in the national spotlight, let alone do so over a rigorous 82-game season. He had never played against an NBA power forward or center, who knew how to bend the rules to stop you from scoring. At Maryland, Joe was the man among boys; he had never come across a Charles Oakley, a notoriously rugged defender and rebounder, or Charles Barkley, a sharp-elbowed, trash-talking superstar. Smith was used to dominating games with relative ease.

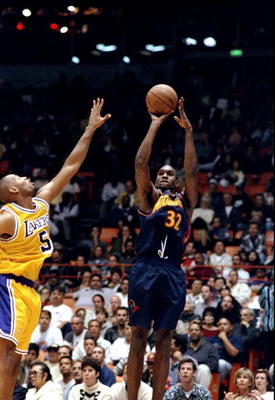

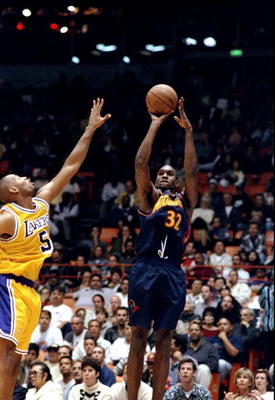

Joe Smith was the man among boys at Maryland, but in the NBA, "it's different.

“At Maryland, it was so much easier because everyone is still learning defensive positioning, team defense, and so many other things, so I could easily take advantage by throwing in a pump fake or making a good cut. Here, you can do all those things, and the guys don’t fall for that,” noted Smith at an interview in Madison Square Garden. “We were playing against talented guys, Duncan and ‘Sheed, but they were still learning. They relied on their athleticism to overcome mistakes. It’s different here.”

This is not to say that Smith’s work ethic should be questioned—far from it. No one practiced harder. But something just didn’t click. Part of it was that Smith was still growing mentally, and was probably rushed prematurely into the world of NBA ball. When he entered the NBA in 1995, he was expected to be a sparkplug for a Warriors squad that never really meshed. And the wear and tear of the NBA season also exacted a price on Smith, who didn’t yet have the endurance to play a full season at a wiry 6’10”, 225 lbs., against the likes of Karl Malone, Barkley, Mutombo, and others.

Even worse, fans and pundits forgot that Smith too, was still learning along the way. You can’t expect a college star to make a seamless transition into pro ranks. So Joe applied a lot of pressure on himself to perform, and was crushed by his inability to dominate as he knew how to. His shooting percentage was low, his rebounding was pedestrian compared to other bigs in the league, and his scoring average reached its plateau at 18 ppg. Meanwhile players drafted after him were tearing up the league.

Players drafted after Joe Smith in 1995 were already tearing up the league while Joe Smith struggled to live up to expectations.

This season, Joe Smith has benefitted from playing in relative anonymity for the New York Knicks. Sure, he was named an All-Star, but that is more of a product of a weak pool of centers and power forwards than it is a testament to Smith’s performance. Playing alongside guys like Sprewell, John Stockton, Allan Houston, and Marcus Camby has helped Smith find a niche and thrive in it. He doesn’t have to carry the team, he just has to contribute in his own way. At face value, Smith’s numbers are awfully pedestrian. At center, he’s averaging 13.8 points and 9.4 rebounds per game, hardly impressive numbers for a former 1st overall pick. But on these Knicks, his contributions are part of a larger team effort to win games and play solid defense. Smith is one of the guys, alongside former college standouts like Camby (himself a former Naismith Recipient), Heisman Trophy winner Charlie Ward, and Kurt Thomas who prefer to play the game right rather than sit in the limelight.

As a Knick, Joe Smith is happy to be one of the guys, alongside former college standouts Marcus Camby and Kurt Thomas

“I think he’s finally found a place to belong and contribute here,” said Ward. “Fans here care more about playing hard, and if you can at least do that, they’ll respect you.” Smith himself said, “I’m teammates with guys like Thomas, who led the NCAA in scoring, with Camby, who was Player of the Year after me, with Sprewell… these are all guys who know what it’s like to deal with adversity and doubt, and they’re all teaching me.” In the Knicks’ system, the game revolves around the guards, and then flows to versatile post men who will consistently hit open shots to keep the floor spread. The centrifuge in many ways is more Marcus Camby, whose athleticism helps extend possessions and get defensive stops. All Smith has to do is rebound, play good defense, hit the open shot, set picks, and take opportunities whenever it makes sense. These are all average things, and Joe Smith does them well.

New York is becoming a sports town of redemption, a place where basketball players fight to win, and in so doing, make or reclaim a name for themselves. Yet, even in a town that buzzes like New York, an average Joe can shine.

Professional sports can be awfully unforgiving to athletes who don’t deliver. And the weight of the basketball world was lumped onto the shoulders of an athletic, well-rounded power forward with an average name: Joe Smith.

When you’re drafted 1st overall, you are expected to be extraordinary, a game changer, a veritable star. But drafting players is an inexact science. The draft is based on data gathered on young men who dominate at the high school and college level, where they are essentially men among boys. What scouts and general managers often cannot measure are the intangibles: the will to win, the willingness to play hurt, the drive to improve and to leverage your skill set into a successful role in the professional world, where everything is faster, rougher, and more unforgiving. Sure, you can show the will to win in the NCAA tournament, but on any given play, college players make at least a half-dozen positioning errors that make it easy for a superior peer to exploit. Professionals might make the same mistake, but they are quicker to recover and more willing to pound you in the process. The greater likelihood is that savvy pros will feign a weakness, and instead quickly deny you the opportunity you seek.

That’s why, in retrospect, basketball experts viciously attacked the Philadelphia 76ers for passing on Penny Hardaway, Jamal Mashburn, Vin Baker, and Allan Houston to draft Shawn Bradley, who has carved out a decent role in this league, but has never been able to come close to justifying his selection at #2 with so much superior talent available.

It is the inexact science of drafting that led to the creation of Joe Smith, the oft-maligned, steady power forward who was chosen instead of Kevin Garnett, Antonio McDyess, and Jerry Stackhouse—all superior players in terms of mental strength and output. Scouts looked at Joe Smith and saw a younger player oozing with talent, a consensus Player of the Year and a future star. He had range, he had athleticism, he had a nice array of moves, and he had a level head. They reasoned that choosing a sophomore allowed teams to develop a young star early and maximize his potential, rather than picking a senior, who can be seen as a prospect with stunted growth from playing against college-level talent for so long. If Smith panned out, basketball executives argued, he could become a real superstar, a guy with a fantastic inside-outside game with the amiability that would make marketing executives drool. Smith could shoot threes, run with small forwards, leap over players, and finish dunks with aplomb.

But choosing a young player has its drawbacks. Barely 20 when drafted, Smith had no clue what it was like to carry a team in the national spotlight, let alone do so over a rigorous 82-game season. He had never played against an NBA power forward or center, who knew how to bend the rules to stop you from scoring. At Maryland, Joe was the man among boys; he had never come across a Charles Oakley, a notoriously rugged defender and rebounder, or Charles Barkley, a sharp-elbowed, trash-talking superstar. Smith was used to dominating games with relative ease.

Joe Smith was the man among boys at Maryland, but in the NBA, "it's different.

“At Maryland, it was so much easier because everyone is still learning defensive positioning, team defense, and so many other things, so I could easily take advantage by throwing in a pump fake or making a good cut. Here, you can do all those things, and the guys don’t fall for that,” noted Smith at an interview in Madison Square Garden. “We were playing against talented guys, Duncan and ‘Sheed, but they were still learning. They relied on their athleticism to overcome mistakes. It’s different here.”

This is not to say that Smith’s work ethic should be questioned—far from it. No one practiced harder. But something just didn’t click. Part of it was that Smith was still growing mentally, and was probably rushed prematurely into the world of NBA ball. When he entered the NBA in 1995, he was expected to be a sparkplug for a Warriors squad that never really meshed. And the wear and tear of the NBA season also exacted a price on Smith, who didn’t yet have the endurance to play a full season at a wiry 6’10”, 225 lbs., against the likes of Karl Malone, Barkley, Mutombo, and others.

Even worse, fans and pundits forgot that Smith too, was still learning along the way. You can’t expect a college star to make a seamless transition into pro ranks. So Joe applied a lot of pressure on himself to perform, and was crushed by his inability to dominate as he knew how to. His shooting percentage was low, his rebounding was pedestrian compared to other bigs in the league, and his scoring average reached its plateau at 18 ppg. Meanwhile players drafted after him were tearing up the league.

Players drafted after Joe Smith in 1995 were already tearing up the league while Joe Smith struggled to live up to expectations.

This season, Joe Smith has benefitted from playing in relative anonymity for the New York Knicks. Sure, he was named an All-Star, but that is more of a product of a weak pool of centers and power forwards than it is a testament to Smith’s performance. Playing alongside guys like Sprewell, John Stockton, Allan Houston, and Marcus Camby has helped Smith find a niche and thrive in it. He doesn’t have to carry the team, he just has to contribute in his own way. At face value, Smith’s numbers are awfully pedestrian. At center, he’s averaging 13.8 points and 9.4 rebounds per game, hardly impressive numbers for a former 1st overall pick. But on these Knicks, his contributions are part of a larger team effort to win games and play solid defense. Smith is one of the guys, alongside former college standouts like Camby (himself a former Naismith Recipient), Heisman Trophy winner Charlie Ward, and Kurt Thomas who prefer to play the game right rather than sit in the limelight.

As a Knick, Joe Smith is happy to be one of the guys, alongside former college standouts Marcus Camby and Kurt Thomas

“I think he’s finally found a place to belong and contribute here,” said Ward. “Fans here care more about playing hard, and if you can at least do that, they’ll respect you.” Smith himself said, “I’m teammates with guys like Thomas, who led the NCAA in scoring, with Camby, who was Player of the Year after me, with Sprewell… these are all guys who know what it’s like to deal with adversity and doubt, and they’re all teaching me.” In the Knicks’ system, the game revolves around the guards, and then flows to versatile post men who will consistently hit open shots to keep the floor spread. The centrifuge in many ways is more Marcus Camby, whose athleticism helps extend possessions and get defensive stops. All Smith has to do is rebound, play good defense, hit the open shot, set picks, and take opportunities whenever it makes sense. These are all average things, and Joe Smith does them well.

New York is becoming a sports town of redemption, a place where basketball players fight to win, and in so doing, make or reclaim a name for themselves. Yet, even in a town that buzzes like New York, an average Joe can shine.